Rust Async Runtimes Explained

The goal of this post is to explain what an async Runtime is in Rust and help build an intuition and mental model for what is going on behind the scenes. The goal is not to become or expert nor is it to understand the performance trade-offs involved with async Rust or why you would use it. This post also intentionally leaves out the topic of non-blocking I/O to try and keep things simple. The intended audience is someone with very little experience with Rust, programming languages, and concurrency, but hopefully people with more advanced knowledge can also get some value out of it.

I personally find this topic confusing and am by no means an expert. So if I say something that’s incorrect, please let me know and I will correct it.

If you haven’t already, I would strongly recommend reading all of the Rust book, but more specifically Chapter 17, which focuses on asynchronous programming.

The Before Times

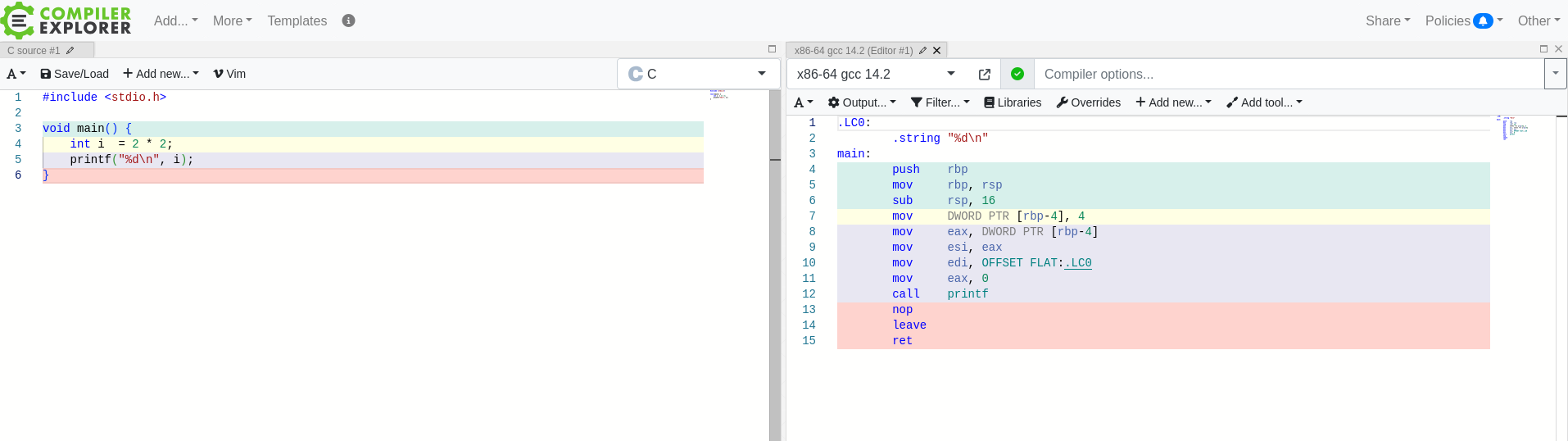

Many low level and older programming languages do not have a runtime environment. The code you write is directly translated to assembly and that assembly is directly ran. Only code that you have directly written (or imported) will be run by the computer. For example, in C and C++ you compile your code to a single binary (usually), and when the binary begins execution it starts execution at your main function, and continues executing the assembly of code until the main function exits.

For example when compiling the following C code to assembly, we can mostly match up each line of the compiled assembly a line in the C code.

Rust, by default, also falls into this category. It has no runtime, by default, and so when executing a compiled Rust program, the execution starts directly at your main function. If we look at the same function in vanilla Rust, the assembly is a bit more verbose, but it looks similar.

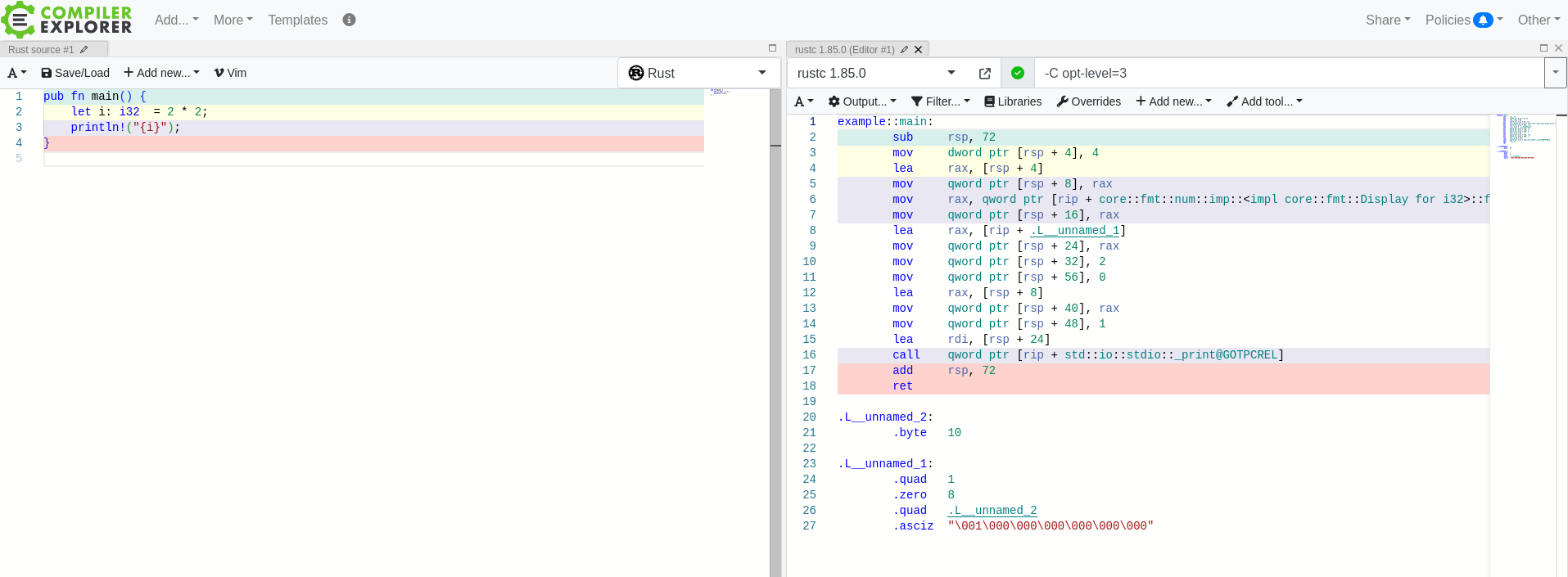

Godbolt

As an aside, Godbolt is a useful website that allows you to visualize compiled code. If you hover over a line of assembly, it will highlight the line of source code that it corresponds to.

Concurrency

If I have a computer with a single CPU and my program creates a new process or thread, then how does one process start and another one begin? I never write code to explicitly stop executing one process and start executing another, so how does that happen? This is the responsibility of the operating system (OS), specifically the kernel. The kernel keeps track of all the running processes and threads on a computer, and is responsible for scheduling and de-scheduling processes onto one of the CPU cores.

Well Actually …

You might actually say that the standard library of a language is a runtime environment, or that the kernel itself is a runtime. That might be true, and there are some interesting/useful parallels to draw between the kernel and other runtime environments, but words are made up and for the purposes of this post it’s easier to consider those as not being a runtime.

Also, the Rust compiler will inject assembly into your binary that you didn’t directly write. This assembly is used to call the drop method of variables that fall out of scope. For the purposes of this post we’re not considering this to be part of the runtime environment either.

Runtime Environments

There are some programming tasks that are extremely common and also extremely difficult. A classic example of this is memory management. Almost every non-trivial program needs to allocate memory on the heap and then later de-allocate that memory, yet it is extremely hard to do it correctly without leaking memory. It would be really nice if your programming language could do these tasks for you so you can focus on more important things. This is where a runtime environment can come to the rescue. A runtime is the environment in which your code runs in; it’s the code that runs your code. So instead of program execution starting at your main function (or equivalent), the program execution starts in the runtime’s code. The runtime is then responsible for calling and running your code. The runtime has the opportunity to sometimes not run your code and instead perform those other useful tasks.

Java

In Java, the JVM is the runtime. The JVM is responsible for running your application, and infamously for sometimes not running your application so that it can clean up unreachable heap memory.

Go

Go compiles a runtime into every program. So when a Go program starts executing, it starts executing the runtime, which eventually calls your main function. If we take a look at the same program as before in Go, we can see references to the runtime, before our main function is called.

Python

In Python, and other interpreted languages, the interpreter acts as the runtime. The interpreter is responsible for calling your source code.

Rust Runtimes

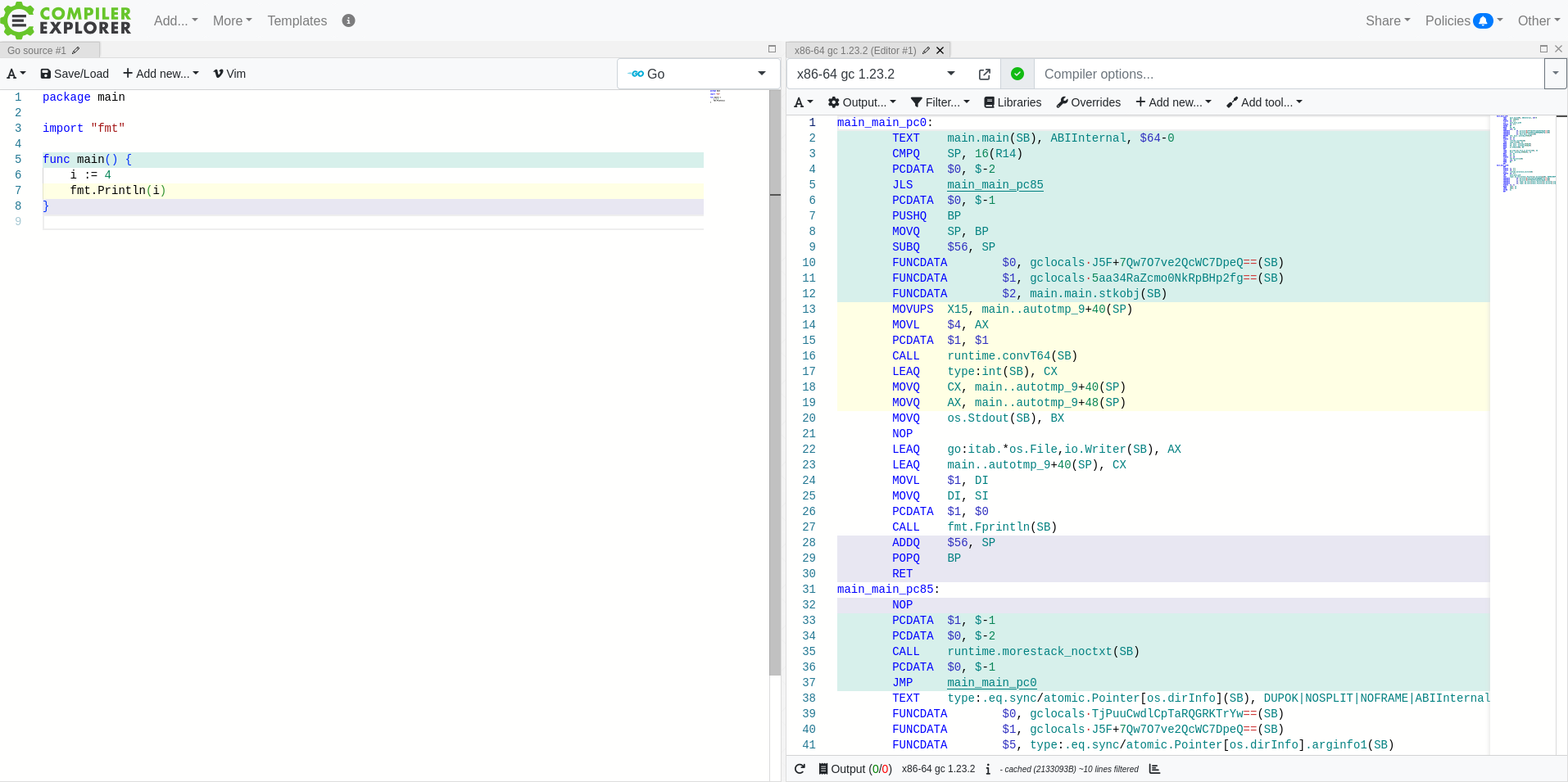

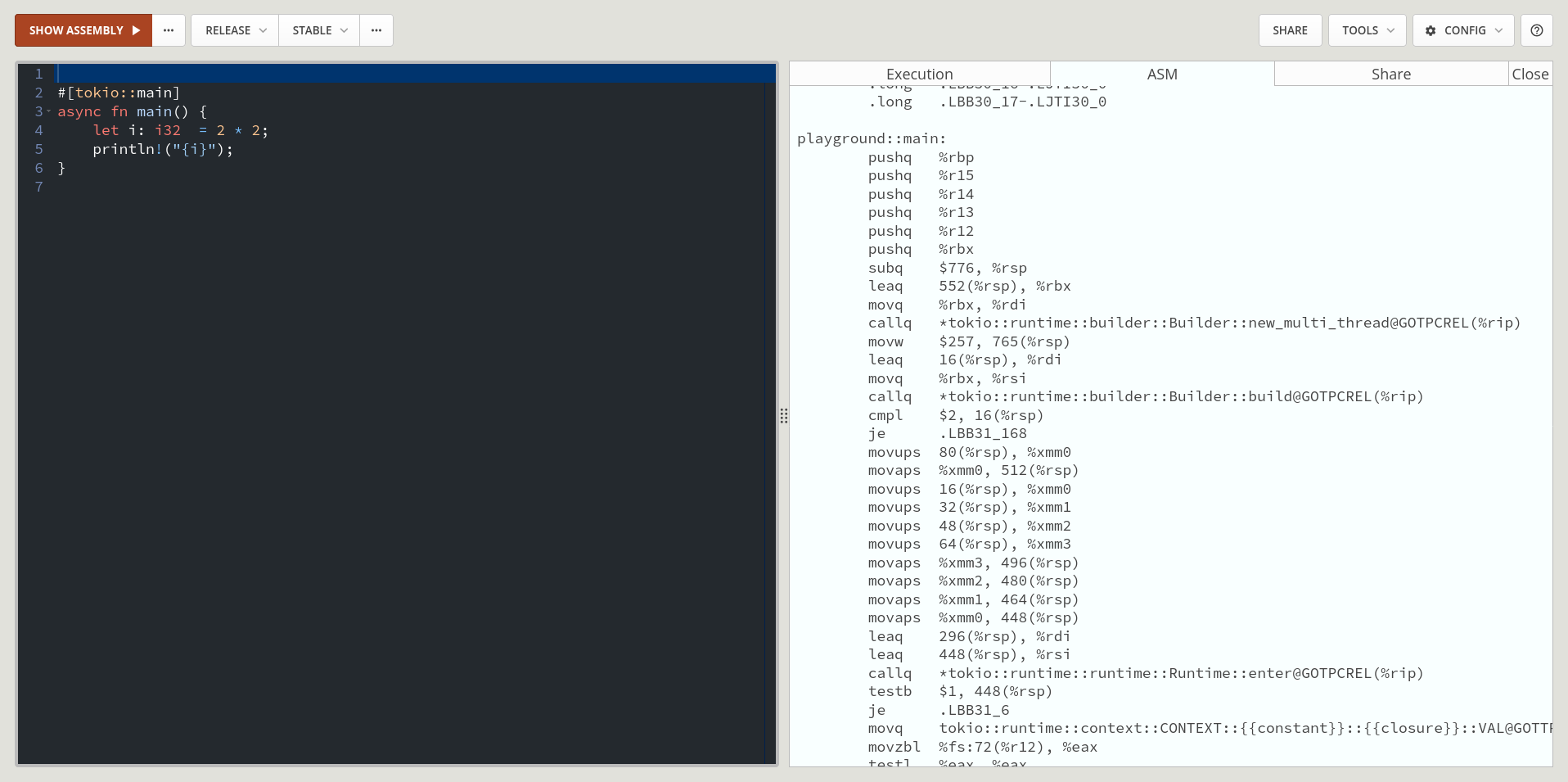

As mentioned previously, Rust does not have a runtime by default. However, we have the ability in Rust to add a runtime if we want. Most applications these days use the tokio runtime. This explains why they have to annotate their main function, like this:

#[tokio::main]

async fn main() {

...

}

The #[tokio::main] annotation tells the compiler that our main function is no longer the entry point to our program. The tokio::main function is the entry point, which should then call our main function. If we look at the same program as before, now with the tokio annotation, the assembly becomes much more complicated and is filled with calls to tokio functions.

Generally as a programmer you never interact directly with the runtime, things usually happen auto-magically behind the scenes. One common exception is to configure the runtime at the start of the application; things like disabling/enabling work-stealing and configuring the number of worker threads. There is an API that you can use to interact with the runtime, but it’s fairly uncommon to use the API directly in user code.

Why would someone want to add a runtime to Rust? For async! If you want to use async in Rust, then you must add a runtime.

Rust Playground

As an aside, Rust Playground is another useful website that allows you to execute visualize compiled Rust code. It is specific to Rust and contains more Rust specific functionality (like access tokio for example) than Godbolt.

User Threads

As mentioned previously, it is the responsibility of the kernel to schedule threads. There has been a trend in recent years to have the ability to schedule and de-schedule units of work completely in user space, i.e. without involving the kernel. The reason that someone would want this is out of scope for this post, but there’s plenty of literature online. This feature comes in all different shapes, sizes, and names, but the one thing they have in common is that they schedule work completely in user space. You may have heard the terms “green threads”, “asynchronous tasks”, “virtual threads”, “fibers”, or “coroutines” which are all different variations of this idea. The difference between them are out of scope for this post. async is Rust’s implementation of this idea.

So, if the kernel is not scheduling these tasks, how do they get scheduled? Do programmers need to write code to explicitly schedule and de-schedule tasks in their code for every program they write? Once again runtimes can come to the rescue. The runtime is already responsible for running our code, and it is run in user space, so it can be responsible for scheduling our tasks. Most runtimes use an event loop which looks something like the following massively simplified program:

loop {

for task in tasks {

task.make_some_progress();

}

}

The runtime keeps track of all incomplete tasks, constantly loops over each one, and makes a little bit of progress on each task. Once a task is complete, the runtime removes it from the list. In reality, the runtime usually maintains a pool of threads and has one loop per thread.

Progress

An obvious question that someone might have is, what does “a little bit of progress” mean? When does the runtime stop running one task and move on to another? Different languages and different implementations take different approaches for this.

In Go, user level threads are called Goroutines. Go uses preemptive scheduling, which means that it can interrupt one goroutine and start another at any time. How Go makes these decisions is out of scope for this post.

Rust uses cooperative scheduling for asynchronous tasks. That means that it’s the programmers job to tell the runtime when it can stop running a task. This is the job of the await keyword, await is a signal to the runtime that you can stop running one task and move on to the next one. Therefore, task.make_some_progress() will not return until it hits an await point. That is the reason why it’s really bad to call synchronous blocking code from an async function. Your program will sit there and do nothing, starving out all other tasks, until the blocking code is complete. It cannot switch to a different task because there is no await point. That is an easy to make mistake which will quickly turn your program into a single threaded sequential application. This blog post does a good job of explaining the issue of blocking in async code.

Function Colors

An async function in Rust is actually just syntactic sugar that the compiler converts into a state machine. So if we have the following asynchronous function:

async fn some_task() {

// Do some stuff.

do_some_file_io().await;

// Do some more stuff.

do_something_else().await;

}

The compiler will convert this into something like the following simplified state machine (Note, this isn’t exactly what the state machine will look like, but works as good mental model):

enum State {

Step1,

FileIO,

Step2,

Done,

}

struct SomeTask {

state: State,

}

impl SomeTask {

fn new() -> Self {

Self { state: State::Step1 }

}

/// Return true if execution is complete, false otherwise.

fn make_some_progress(&mut self) -> bool {

match self.state {

Step1 => {

self.step_one();

self.state = FileIO;

false

}

FileIO => {

if self.file_io_is_done() {

self.state = Step2

}

false

}

Step2 => {

self.step_two();

self.state = Done

true

}

Done => {

true

}

}

}

fn step_one(&mut self) {

// Do some stuff.

do_some_file_io();

}

fn file_io_is_done(&self) -> bool {

// Check if File I/O is done.

}

fn step_two(&mut self) {

// Do some more stuff.

do_something_else();

}

}

There’s one massive simplification/omission in the above code. do_some_file_io() and do_something_else() are both async functions. So they both may contain additional await points, which may yield execution of the task. Therefore, the state machine actually needs to be defined recursively.

Tokio is responsible for keeping track of all the state machines in a program, and calling make_some_progress on all of them in a loop.

This hopefully also explains why a non-async functions cannot call an async function. The async function is converted into a state machine, and the non-async function has no idea what to do with the state machine. async functions must be called by another async function or by an asynchronous runtime. This Stack Overflow post also goes into more details on this topic. non-async functions can be called by async functions, because they are just normal functions; execution can start at the beginning of them and continue to the end of them without interruption.

If you’re a visual learning, you can picture a programs call stack as a directed graph. Each node is a function and there is an edge from f1 to f2 if f1 calls f2. A node must be async if any of it’s children are async.

Async functions can sometimes have a viral nature, if a single functions is async, then the root of the graph (i.e. the main function) and every node in-between needs to be async. The notion of having two separate kinds of functions is sometimes referred to as a function color, which was made popular by this blog post/rant.

Cancellation Safety

If you don’t want to be confused by cancellation safety, then skip this aside. Understanding the above state machine may also help understand the concept of cancellation safety. An asynchronous task can be cancelled under some contexts, most commonly when using the select! macro. When a task is cancelled, it’s execution is stopped, and then potentially later restarted at the previous await point. For example, step_one() from our state machine might stop execution in the middle and restart later from the top of the function. Cancellation safety describes whether or not this is safe. Does your function append text to a file? Then you might append the same text twice. Does your function remove a message from a queue? Then you may lose the message and never process it. Cancellation safety is the source of many subtle and annoying bugs.

Multiple Runtimes

The original motivation for this post was to answer the question, does it make sense to have multiple runtimes in an application? So I want to take a brief moment to discuss this idea.

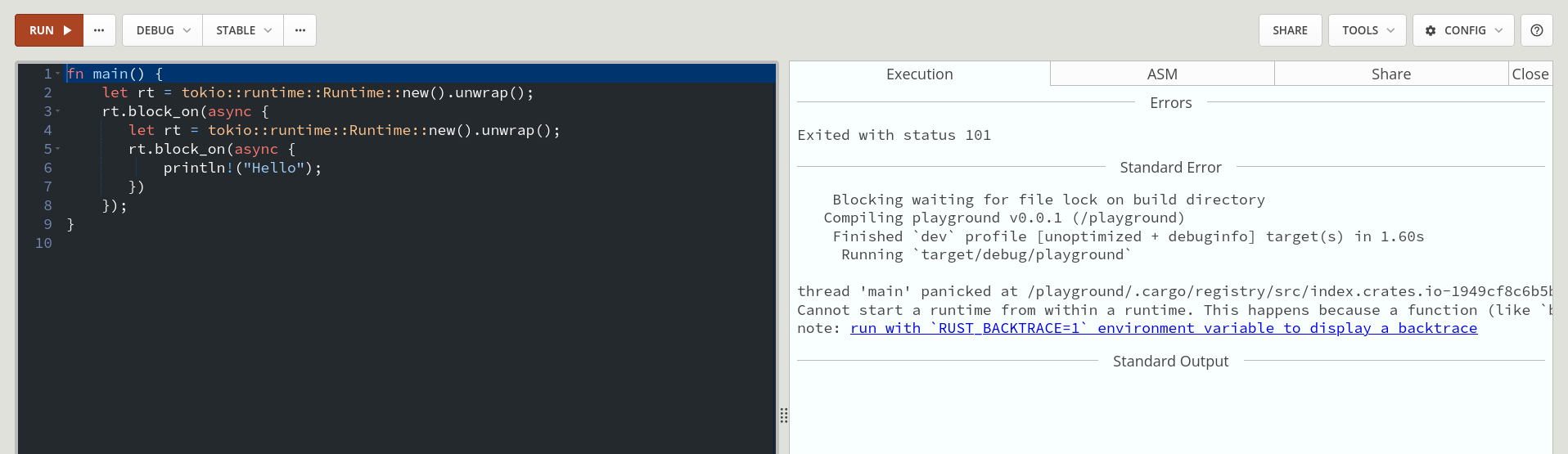

Nested Runtimes

Running a runtime within a runtime is not allowed and will result in a panic. The simple reason is that the code for the runtime is synchronous blocking code. As discussed earlier, you shouldn’t run synchronous blocking code in an asynchronous context or you’ll starve out other tasks.

From a conceptual point of view, it’s not clear why someone would ever want this. The runtime adds some non-zero overhead (it has to run runtime code that isn’t your application’s code). So a nested runtime means that for each nested task you have to pay this cost twice.

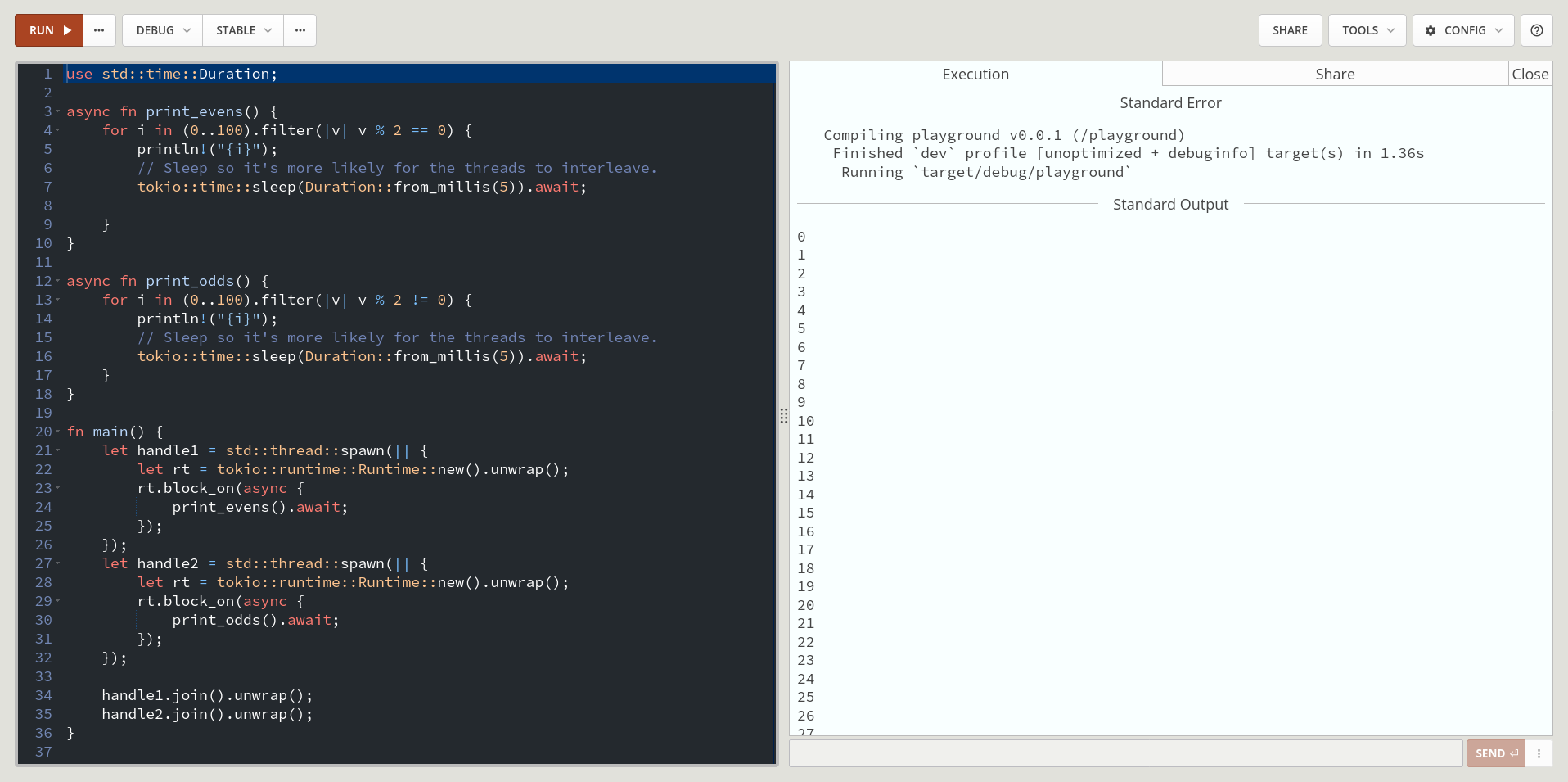

Independent Runtimes

It is possible to run two independent runtimes, as long as they each have their own independent pool of threads.

However, from a conceptual view, it’s again not clear (to me) why someone would want this. Fundamentally, the runtime’s job is one of resource management. Given a set of physical resources and a set of user defined work, how can we most efficiently schedule this work onto the resources. The kernel makes a good scheduler because it has a global view of all system resources and all processes running on the system. It can make very informed decisions with this global view. The Rust async runtime knows about the system resources and the tasks run in the context of that runtime. As you create more runtimes, each runtime has less of a global view of the application and can make less informed decisions. Additionally, you are now more reliant on the kernel to schedule each runtime’s threads. This would be similar to a Java application creating multiple JVMs and running different parts of the application on different JVMs.

So, is this ever desirable? It turns out that I do not know the answer to this question. Maybe it is sometimes? Potentially it provides some form of isolation between runtimes. Potentially it allows you to separate tasks by priority? If a reader of this knows the answer, then please let me know. However, I do think it’s clear that multiple runtimes shouldn’t be used without a good reason, because it does introduce inefficiencies into your application.

Runtime Overhead

One question someone might ask is, does a runtime add any overhead? Strictly speaking yes, when using a runtime your spending cycles running code that isn’t your application’s code, which is going to add some amount of latency. Then why would anyone use a runtime? Like most things in programming it’s about tradeoffs.

Garbage Collection

Garbage collecting runtimes reduce memory related bugs, simplify programs, and increase developer velocity. If you’re writing an application that isn’t concerned with low latencies, then this might be a worthwhile tradeoff. Some of these runtimes are infamous for “stop the world” GC pauses, where the application is completely halted for some amount of time to clean up unreachable memory. This can absolutely destroy an applications performance.

Portability

Some runtimes can help with application portability. With fully compiled languages, like C, C++, Rust, and Go, you need to re-compile your program for different architectures. Interpreted languages like, Java and Python, generally only need to be compiled once or not at all. As long as an architecture has an implementation of the runtime, your program will run there. This used to be one of Java’s big selling points, “Write once, run anywhere”.

Async Runtimes

While async runtimes add the latency of executing the runtime code, they also reduce the latency and memory usage associated with creating and switching between OS threads. Overall, do you end up with reduced latency? That depends on the application. If you’re running a single threaded application with no concurrency, then probably not. If you’re running a program with thousands of concurrent tasks, then probably.

Putting it all Together

Let’s put everything together. async functions are converted into a state machine by the compiler. Each await creates a new state transition in the state machine. The Tokio runtime is responsible for keeping track of all the state machines in your application, looping over them, and making some progress on each one that is ready to make progress. The ultimate goal of this is to run multiple concurrent units of work without involving the kernel.